In a rural area of West Africa, a three-year-old child is admitted to the local hospital with abdominal pain and decreased responsiveness after a witnessed seizure.

This case will guide you through a clinical encounter to understand the patient's health challenges – and how to respond.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Understand how toxic exposures can manifest in both humans and animals

Explain how to follow up concerns about animal health disease events – consult with other professionals including veterinarians, environmental health and public health experts

Explain how toxic exposures are related to environmental change

CLINICAL COMPETENCIES

Assess history of toxic exposures

Develop a differential diagnosis and utilize appropriate diagnostic testing for suspect heavy metal toxicity

Recognize sentinel cases (human and animal) of toxic exposure

Apply the host-environment approach to the management of a toxic exposure

A Continuing Medical Education activity presented by the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health and the University of Washington. View CE information and claim credit HERE.

Accreditation

In support of improving patient care, Stanford Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Credit Designation

American Medical Association (AMA)

Stanford Medicine designates this Enduring Material for a maximum of 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC)

Stanford Medicine designates this Enduring Material for a maximum of 1.5 ANCC contact hours.

American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA)

Stanford Medicine has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credit for activities planned in accordance with AAPA CME Criteria.

This enduring activity is designated for 1.5 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. Approval is valid until December 14th, 2026. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

Clinical Approach

Consider the following questions as you work through this case:

Hazard identification

Based on the patient’s history, what could they be exposed to?

Exposure & risk assessment

How much exposure has the patient had? How much is the patient at risk?

Treatment & exposure reduction

Treat the patient, focusing on improving host factors. Identify strategies to reduce the patient’s exposure going forward.

History

Taking a clinical history of your patient yields the following information:

Chief complaint

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea and vomiting

History of present illness

- Lost appetite and fatigue over past month

Past medical history

- No history of seizures or other neurological problems

- Was born at term with no pregnancy or neonatal complications

- No known medical problems

- No head trauma

Medications

- None

Family history

- N/A

Social & enviromental history ("Social-E")

- Mother reports that several other children in the village are also sick with similar symptoms

Review of systems

- No fever or rashes

- No head trauma

- No diarrhea (in fact, constipated)

Discussion

What additional information would you want to know?

Given the lack of fever, what non-infectious causes would you consider?

If you are considering a toxic exposure, how would you ask about that?

Key History Follow-Up Questions

Asking your patient the following questions gives you this information:

What is your home made of? What about the floors? Is there old and peeling paint?

- Dirt floors can become contaminated. Paint, especially old peeling paint, can be a source of lead.

- Patient lives in a home with dirt floors. She spends days playing around the family compound and does not wash hands regularly before eating. She has been seen eating dirt.

What types of work do you do – are you exposed to toxic chemicals?

- Occupational exposures are very important.

- Patient is a child (not formally employed).

Is anyone else sick?

- If there are toxic exposures at work or elsewhere, usually more than one person is affected.

- Mother reports that several other children in the village are also sick with similar symptoms.

Do you have any hobbies, home businesses, or other activities that involve chemicals?

- Many home businesses or hobbies, such as jewelry making, can involve chemicals that can directly expose persons or contaminate the home environment. In many parts of the world, home businesses can include artisanal mining for gold or other metals.

- The mother, as well as several neighbors in the village, had become engaged in artesanal (small-scale) gold mining activities in the home over the past year, including breaking, grinding, and drying ore. This had produced a lot of dust around the family compound.

What is your source of water?

- Water can be a source of many toxic chemicals, including arsenic and lead.

- Patient drinks unfiltered water.

What is your contact with dust or dirt?

- Food and economic insecurity can lead to malnutrition and pica. Recent crop failures due to drought have increased food and economic insecurity in the village.

- Family reports child has been crawling in and eating dirt.

Are you aware of any pollution sources or work with chemicals near your home?

- Nearby industries could be releasing toxic chemicals.

- Family is not aware of any pollution sources.

Are pesticides used nearby?

- Human exposure to pesticides, especially children, can lead to short-term and long-term health impacts, such as headache, dizziness, and nausea, among other symptoms.

- Family reports patient has not been exposed to pesticides (that they know of).

Have you heard of any sick or dead animals near where you live?

- Animals may be highly exposed and act as “sentinels” for environmental hazards, exhibiting symptoms or dying before human risk is recognized.

- Over the past year, ducks in the nearby lake have disappeared. A number of dogs, goats, and other livestock in the village have died recently without a known cause.

Discussion

What could be the exposure?

What are clues from the patient’s history so far?

What are hazards associated with small-scale gold mining, particularly grinding and drying ore?

How does food security relate? History of eating dirt?

How can you interpret deaths of ducks, dogs, goats, livestock?

Physical Exam

When you examine your patient, you learn the following:

General

- Sick-appearing child, only minimally responsive

- Temperature 37 C, heart rate 130 BP 120/85, heart regular

HEENT

- Pupils equal and responsive, pale conjunctiva

- Gingival hyperpigmentation

Neck

- Neck supple

Chest & lungs

- Chest clear

Cardiovascular

- Unremarkable

Abdominal

- Abdomen with diffuse tenderness, liver slightly enlarged

Skin

- No skin lesions

Musculoskeletal

- Unremarkable

Neurological

- Responds only to painful stimuli

- Reflexes 0-1+

- No meningismus

- Movements symmetric

Many toxic exposures do not have specific findings. For this reason, the history is critical!

Physical exam suggests both neurological and gastrointestinal involvement.

Lack of fever argues against infectious cause.

“dark line in gums is consistent with lead poisoning.

History of parent involved in mining activities in home suggests toxic exposure.

Information on other symptomatic children is important. Have they also been exposed?

Key Points

Consider the following as you INTERPRET the physical exam:

Discussion

What are your clinical concerns?

How does this patient’s exposure history influence your differential diagnosis?

How does the history of sick animals affect the differential diagnosis?

With this clinical setting in mind, what labs and/or imaging would you pursue?

What additional diagnostic testing would you pursue?

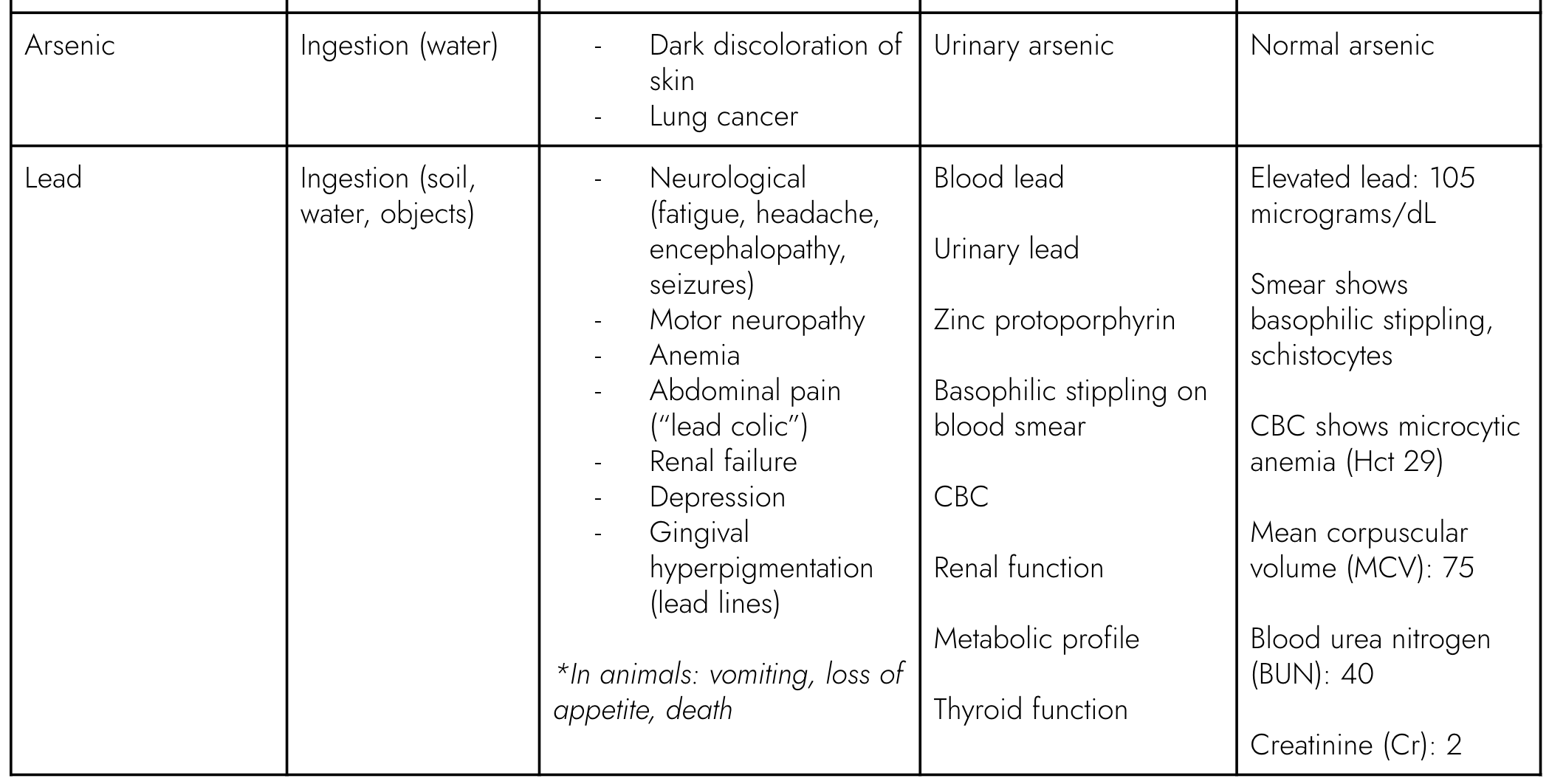

Diagnostics

This table shows several heavy metal syndromes and the kind of tests that can be ordered:

*Many labs offer a urine heavy metal screen: lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury

Infectious

Meningitis: viral, bacterial, or other

Cerebral malaria

Encephalitis

Tuberculosis

Toxic

Heavy metal poisoning: mercury, lead, arsenic

Pesticide poisoning

Chemical – ethylene glycol, etc.

Other toxic exposure: algal toxins, ergotism, medications, etc.

Other

Appendicitis

Liver failure: Reyes syndrome, etc.

Renal failure: Hypo- or hypernatremia

Differential Diagnosis

the patient’s symptoms might indicate the following:

Final Diagnosis

arriving at a conclusion:

Diagnosis: Acute Lead Poisoning

Lead level markedly elevated (105 mcg/dL); with encephalopathy and abdominal signs and symptoms is consistent with severe lead toxicity.

Labs suggest ongoing hemolysis – the destruction of red blood cells (RBCs), which here seems to be a result of lead exposure.

For lead, toxicity is determined by the dose. This patient’s venous lead level of 105 µg/dL puts her at very high risk.

5 µg/dL: CDC limit for children- subclinical effects possible

10 µg/dL: CDC limit for adults

45 µg/dL: consider chelation therapy in children

70 µg/dL: hemolysis, neurological effects often seen

100 µg/dL: seizures, death common

Lead poisoning in children often co-occurs with iron and other nutritional deficiencies, as well as pica (an eating disorder in which a person eats things not usually considered food).

Oral chelation therapy (e.g., with DMSA)

Manage seizures (e.g., with benzodiazepine)

Ensure adequate hydration

Assistance for cognitive impairment

Management & Treatment

You can help your patient in the following ways:

Prevention

reducing vulnerability and exposures:

Reducing host vulnerability / susceptibility (host factors):

Assess nutritional status, treat iron deficiency.

Reducing exposures / improving environments (environmental factors):

Stop the generation of contaminated dust. This means stopping gold mining activities, moving them away from dwellings, and/or reducing dust generation through wetting and other tactics.

Test and remediate (remove) contaminated soils.

Improve hand hygiene.

Restrict access to contaminated areas.

Replace dirt floors.

One Health is an approach that considers linkages between human, animal, and environmental health

In this case, interdisciplinary teams of human health professionals, veterinarians, and environmental health experts worked together to investigate cases in humans and animals and remediate the lead exposure.

Beyond the Clinic

Your patient's story is part of a bigger picture:

Animals can be sentinels for toxic exposures relevant to humans, since they share exposure routes (ingestion, direct contact, inhalation), often have greater exposure, can be more susceptible to toxic effects, and have shorter lifespans. In this case, documented cases of dogs, cats, and livestock showing symptoms before humans can provide clues for diagnosis. Consulting with veterinarians – who can test animals and share findings – can help identify shared exposures.

In addition to veterinarians, environmental health professionals can follow up on toxic exposure concerns. Clinicians should get in contact with health departments and departments of ecology and natural resources to share their concerns.

Local environments can become contaminated with toxic substances – including the dust, soil, and water. Clinicians should consider possible toxic exposures and routes of exposure, such as food and water ingestion, inhalation and ingestion of dust, and direct contact with certain toxins that can be directly absorbed through the skin.

Extractive industries are sources of environmental contamination. This includes oil and gas drilling, which can create exposure to volatile organic compounds, and gold mining, as in the case of this patient, which can put local communities at risk of mercury and lead contamination. Clinicians can leverage their clinical findings to advocate for broader environmental change.

Case Follow-Up

What happens next:

In this case study, home processing of gold ore activities had begun during the past year in the villages. To find out more, the Ministry of Health, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), the national Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP), and the CDC carried out investigations. Surveys in two villages found that as many as 25% of the children younger than 5 – over 100 children in total – had died in the past year with a history of convulsions consistent with lead poisoning. Furthermore, lead testing of over 200 children found that 97% were above the limit for chelation (45 mcg/dL). More than 160 children received chelation. Lead concentrations in the soil and dust ranged from 45 parts per million (ppm) to >100,000 ppm; 85% of family compounds exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standard (400 ppm) for areas where children are present.

Joint environmental health and veterinary teams carried out the removal of contaminated soil and assessed local animal health. Follow-up studies found widespread lead poisoning among children in the region due a recent increase in small-scale gold mining, as well as poisoning of chickens and other animals. Overall, an estimated 400 children in the region died of lead poisoning, and over 2000 children among an estimated 17,000 exposed individuals received chelation treatment.

Discussion

What do you think are some ways that pollution affects the health of animals and ecosystems?

What are some ways clinicians can advocate for community, national, and global interventions to address the planetary health impacts of lead and other toxic pollution?

Call to Action

Clinicians can take action to advance planetary health:

At the clinic:

Report cases of toxic exposure in patients

Document trends in case loads over time can provide useful data to policy makers and others

In your community:

Network with other professionals including veterinarians who are dealing with toxic issues in animals

Study the health outcomes from different interventions that aim to reduce exposure to pollutants

At the societal level:

Communicate knowledge of health effects of toxic pollution – and who is most vulnerable – to policymakers

Advocate for policies related to preventing pollution

Advocate for increased testing of high risk groups and of environmental sources

Summary &

Key Learning Points

also available for download here:

Diagnosis:

Recognition of toxic exposures can be lifesaving – history is key.

Clinicians should pursue targeted diagnostic testing based on their differential diagnosis.

Determine the hazard, and the degree of exposure (dose) to determine the risk to the patient.

Sentinel cases (human and animal) can indicate toxic risk in the environment and narrow differential diagnosis. Clinicians can play a key role in detecting sentinel cases. Communication between human health clinicians and veterinarians can improve sentinel detection.

Treatment:

Treat the acute condition, but also utilize a host-environment approach to prevention:

Improve host factors, such as (in this case) iron deficiency.

Reduce ongoing environmental exposures, which could require both working with the patient and broader community.

The big picture:

While individual-level interventions can help to reduce toxic pollution exposure, particularly in the short term, personal harm reduction measures are not nearly sufficient.

Populations with greater resource constraints are often at greater risk – for example, in this case, local communities rely on gold mining for income. Advocating for or supporting alternative income-generating initiatives in local communities that otherwise depend on gold mining is key for this risk to be reduced or eliminated.

Efforts to reduce pollution on a national and global scale are essential to creating both meaningful population and ecological health improvements.

“One Health” team approach: human, environmental, veterinary professionals can be useful for following up cases.

References

CDC. Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Acute Lead Poisoning Among Children Aged <5 Years --- Zamfara, Nigeria, 2010 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) July 16, 2010 / 59(27);846

Dooyema CA, Neri A, Lo YC, Durant J, Dargan PI, Swarthout T, Biya O, Gidado SO, Haladu S, Sani-Gwarzo N, Nguku PM, Akpan H, Idris S, Bashir AM, Brown MJ. Outbreak of fatal childhood lead poisoning related to artisanal gold mining in northwestern Nigeria, 2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Apr;120(4):601-7.

Lo YC, Dooyema CA, Neri A, Durant J, Jefferies T, Medina-Marino A, de Ravello L, Thoroughman D, Davis L, Dankoli RS, Samson MY, Ibrahim LM, Okechukwu O, Umar-Tsafe NT, Dama AH, Brown MJ. Childhood lead poisoning associated with gold ore processing: a village-level investigation-Zamfara State, Nigeria, October-November 2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Oct;120(10):1450-5.

Oladipo OO, Akanbi OB, Ekong PS, Uchendu C, Ajani O. Lead Toxicoses in Free-Range Chickens in Artisanal Gold-Mining Communities, Zamfara, Nigeria. J Health Pollut. 2020 May 26;10(26):200606.

Tirima S, Bartrem C, von Lindern I, von Braun M, Lind D, Anka SM, Abdullahi A. 2016. Environmental remediation to address childhood lead poisoning epidemic due to artisanal gold mining in Zamfara, Nigeria. Environ Health Perspect 124:1471-1478; http://dx.doi.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/10.1289/ehp.1510145.