CASE STUDY

Displacement & Refugee Health

A 28-year-old woman recently arrived in the US from Somalia presents to your primary care clinic to establish care.

This case will guide you through a clinical encounter to understand the patient's health challenges – and how to respond.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Define forcibly displaced persons

Illustrate global migration patterns of forcibly displaced persons

Recognize how environmental and political factors contribute to forced displacement and impact the health of migratory populations

CLINICAL COMPETENCIES

Identify the leading health conditions among resettled refugees and migrant populations

Access and apply the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for immigrant and refugee health in the clinical management of a newly arrived refugee

Screen for, diagnose, and treat specific health conditions of concern among refugees presenting for care

Provide preventive care for resettled persons

Provide culturally competent care

Integrate up-to-date resources and guidelines into the clinical management of refugees and migrant patients

A Continuing Medical Education activity presented by the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health and the University of Washington. View CE information and claim credit HERE.

Accreditation

In support of improving patient care, Stanford Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Credit Designation

American Medical Association (AMA)

Stanford Medicine designates this Enduring Material for a maximum of 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC)

Stanford Medicine designates this Enduring Material for a maximum of 1.5 ANCC contact hours.

American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA)

Stanford Medicine has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credit for activities planned in accordance with AAPA CME Criteria.

This enduring activity is designated for 1.5 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. Approval is valid until December 14th, 2026. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

Clinical Approach

Consider the following questions as you work through this case:

Determine geographic history and circumstances of departure:

Country of origin.

Why did patient leave? (e.g., conflict, persecution, famine, drought, flooding, other natural disasters)

Exposures on way: What countries did patient pass through? Specific exposures?

Consider cultural and language issues in all aspects of care

Address specific exposure risks

Infectious

Psychosocial

Other

History

Taking a clinical history of your patient yields the following information:

Chief complaint

- Establish care

History of present illness

- No specific concerns at this time; here to establish primary care

Past medical & surgical history

- No known medical problems or prior surgeries

Medications

- Consumes a tea made from traditional herbs (patient does not know the names in English). No other medications.

Allergies

- No known drug allergies

Family history

- Her family members were killed during conflict. No known family history of medical problems.

Social & enviromental history ("Social-E")

- She arrived in the US 6 months ago. She and her family were farmers in Somalia but lost their livelihood due to increasingly frequent and severe droughts, complicated by civil conflict. She is a widow.

- She is currently housed. She works as a housekeeper at a local hotel. She does not smoke or drink alcohol. She has no recent animal contacts. She lives alone. She does not have family or friends.

Review of systems

- Intermittent abdominal pain. No fevers, chills, night sweats. No cough. No chest pain. Minimal appetite but no recent weight loss. No headaches or vision changes. No nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. No dysuria. Normal menses. No skin changes. Somewhat fatigued, poor sleep due to frequent nightmares.

Discussion

What additional information would you want to know?

Time management: Given the probable complexity of the patient's history and the need for an interpreter, appointments will likely take longer than usual.

Interpreter preference: Offer interpreter services. Ensure the patient that the interpreter will maintain confidentiality.

Cultural context: It is essential to work with a culturally competent interpreter, healthcare worker, and/or patient navigator that will support efforts of communicating the purpose and intentions of the clinician.

Reassurance: Provide reassurance and consistent, clear communication that the clinic is a safe environment.

Age: The patient’s reported date of birth may not be accurate as immigration documents may contain errors. Always verify the patient’s age with the patient as this may have important implications for clinical care.

Past medical history: Different health-seeking behaviors (doctor’s role vs. traditional healer etc.), cultural practices (e.g., cutting, burning, cupping, FGM), attention to differing terminology (e.g., bilharzia vs. schistosomiasis)

Medications: Ask about traditional medicines, herbs, tinctures, etc. Ask the patient to bring the medicine bottles and containers so you can document them.

Review of systems: Patient may use different terminology for symptoms, for example instead of reporting, “pain”, “burning,” patient may say something like “feels like smoke” or “feels like fire (or a serpent or a scorpion…)”

Exposures: Ask about prior living circumstances, urban vs. rural, food and water sources, animal exposures, environmental exposures (e.g., indoor smoke), prior occupation(s), traditional practices

Substance use: Ask about alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, stimulants such as Khat, Kola nuts

Social support: The resettlement experience can be very isolating. Ask about family, friends, community, sources of support.

Housing: Is she housed? Does she have a safe living situation?

Education, literacy: Can she read prescription instructions?

Legal status: This can be a clue to whether the patient had pre-departure screening and health services, but shouldn’t be recorded in the medical record.

Sensitive topics: Approach specific topics with extreme sensitivity, such as discussing sexual history, history of trauma or abuse, torture, rape, witnessed violence.

Key Points: History Taking

CONsider the following as you continue evaluating your patient:

Prior to resettlement, she lived in a refugee camp in Kenya.

In the refugee camp, she was assaulted while out gathering firewood.

While in the camp, she slept under a mosquito net most nights, she had contact with chickens and goats, she did not always have access to safe drinking water, she cooked over a wood fire indoors, and she walked barefoot.

She attended school in the camp, and she is able to read and write.

She migrated to the US via unofficial routes. She traveled through multiple countries in South and Central America prior to her arrival in the US. She experienced mosquito bites and drank unfiltered water.

She applied for asylum status upon arrival.

Additional Patient History

You obtain more information about your patient:

Discussion

What are the global migratory patterns of refugees and displaced persons?

How does knowing the patient’s migratory journey influence clinical decision making?

As of mid-2022, the total number of forcibly displaced people was estimated to be 103 million (UNHCR).

The total number of forcibly displaced people encompasses refugees, internally displaced people, asylum seekers, and other people in need of international protection.

More Context on Displacement

A Growing challenge worldwide:

Forcibly Displaced People: Key Terminology

Information to help contextualize displaced individuals:

Refugee: Someone who has been forced to flee their country because of persecution, war, or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

Internally displaced person (IDP): Someone who has been forced to flee their home as a result of armed conflict, generalized violence, violations of human rights, or natural- or human-made disasters, but has not crossed an international border. Unlike refugees, IDPs are not protected by international law and are ineligible to receive many types of aid because they are legally under the protection of their own government.

Asylum seeker: A person who has fled from their country and has sought international protection, however their claims for refugee status have not yet been determined. Clinicians can be trained in Forensic Medical Evaluations which can be used as evidence for asylum claims.

Physical Exam

When you examine your patient, you learn the following:

General

- Vital signs: 98.6°F/37°C, HR 72, RR 16, BP 120/85

- Appears well nourished, no acute distress.

Head Eyes Ears Nose Throat (HEENT)

- Pupils equal, round, and reactive to light. No scleral icterus, no conjunctival injection or pallor, mucus membranes moist, no oral lesions, poor dentition.

Neck

- Neck supple without meningismus. No masses or lymphadenopathy.

Chest & lungs

- Lungs clear to auscultation bilaterally. No rales, rhonchi, wheezing or stridor. Normal respiratory effort.

Cardiovascular

- Regular rate and rhythm, normal S1 and S2. No murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Warm, well-perfused extremities. No edema.

Abdominal

- Normoactive bowel sounds. Abdomen soft, non-tender, non-distended, no masses or organomegaly.

Skin

- Warm, dry. No rashes. Multiple, uniform, round scars, ~1-2cm in diameter, across chest and abdomen.

Musculoskeletal

- No gross deformities, discolorations, lesions. Tolerates full range of motion of extremities without tenderness.

Neurological

- Alert and oriented to person, place, and time. CN II-XII intact. Sensation grossly intact. Strength 5/5 in bilateral UE and LE. Finger to nose intact bilaterally. Normal gait.

Psychiatric

- Calm, intermittent eye contact, slightly guarded, with otherwise appropriate mood and affect.

Amputations or deformities related to land mines or other explosives are common among certain groups of refugees.

Cultural health practices – including things like cupping and coining, can result in hyperpigmentation or bruising – may mimic torture or physical abuse.

Key Points: Physical Exam

Consider the following as you examine your patient:

Source: Crosby 2013

Source: ethnomed.org

Discussion

With this patient’s history in mind, what are your clinical concerns?

Leading diagnoses among resettled international migrants:

Latent tuberculosis (42%)

Mental health disorders (24%)

Hepatitis B (14%)

Active tuberculosis (9%)

Soil transmitted helminths (9%)

Schistosomiasis (7%)

Malaria (3%)

HIV (2%)

Dental 32%, ophthalmologic 10%, hypertension 5%

Differential Diagnosis

here are some etiologies you should consider:

Source: Boggild et al., 2019; Barnett et al., 2013; McCarthy et al., 2013; Kleinert et al., 2019

Discussion

What screening and/or diagnostic testing would you pursue for this patient?

Guidance for Examination

CONSIDER THE CDC’S GUIDANCE FOR THE MEDICAL EXAMINATION FOR NEWLY ARRIVING REFUGEES AS YOU CONTINUE TO EXAMINE YOUR PATIENT:

Parasites

Sexual and reproductive health

Mental health

Nutrition and growth

Lead screening

Immunizations

Tuberculosis

HIV infection

Viral Hepatitis

Since US-bound refugees are not required to receive vaccinations before arrival, they may not be fully up to date with immunizations.

At the first domestic health visit, clinicians should review all available vaccine records, perform any testing, and update or revaccinate as appropriate.

If vaccination records are unavailable, an age-appropriate vaccination schedule should be initiated.

Checking for laboratory evidence of immunity (e.g., antibody levels) is an acceptable alternative to vaccination when previous vaccinations or disease exposure are likely.

Vaccination Requirements

Consider the following as you establish care for your patient:

CDC requirements:

Varicella

Influenza

Pneumococcal pneumonia

Rotavirus

Hepatitis A

Meningococcal

COVID-19

Immigration and Nationality Act requirements:

Mumps, measles, rubella

Polio

Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids

Pertussis

Haemophilius influenza type B

Hepatitis B

Country of birth is a major risk factor for TB in the US, with the majority of reported TB cases occurring among non-US born persons (71.4%).

Both drug-resistant TB and extrapulmonary TB are more prevalent among foreign-born persons.

Reactivation of latent TB infection (LTBI) is the primary driver of TB disease in the US, accounting for >80% of all TB cases.

It is important to identify and treat LTBI as soon as possible after arrival. Although 13.5% of cases among non-US born persons occurred within one year of arrival in the US, the risk of progressing to TB disease remains high for many years after resettlement, making it essential that clinicians find and treat LTBI before TB disease develops.

Tuberculosis (TB) has been recognized as a climate-sensitive disease. Climate change can contribute to many key risk factors for poor TB outcomes, including overcrowding, indoor air pollution, poverty, and poor nutritional status.

Many developing countries where TB is highly prevalent are especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change on health.

Tuberculosis:

A key disease to consider for forcibly displaced persons:

Source: CDC

One of the most critical risks for healthcare-associated transmission of TB is from patients with unrecognized TB disease who are not promptly handled with appropriate airborne precautions.

Any patient with signs or symptoms of TB disease should have a CXR.

Prompt treatment should be initiated in consultation with an infectious disease specialist or other TB expert.

All presumptive or confirmed cases should be reported to the local health authorities within 24 hours of determination so that appropriate public health measures can be implemented.

TB treatment guidelines are available from the Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Active TB / TB Disease

Transmission of TB is a risk in healthcare settings:

HIV & Migration

HIV screening should be offered to all refugees resettling in the US:

Given the known benefits of early detection, counseling, provision of antiretroviral therapy, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission, HIV screening should be performed on all refugees unless they decline.

Social disruption caused by migration, unsafe living conditions, and discrimination can increase migrants’ exposure to diseases such as HIV and can lead to late diagnosis, poor treatment-seeking behavior, treatment default, and potential for further transmission. Persistent stigma and discrimination towards migrants further increases HIV vulnerability.

Multiple factors increase HIV risk for refugees and migrants, including economic distress, conflict, sexual abuse and violence, oppression, discrimination, exploitation, gender bias, and sociopolitical marginalization.

Refugees are frequently excluded from the national healthcare systems of host countries and voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) may not be accessible.

During the migration process, refugees and migrants living with HIV may lose access to antiretroviral therapy and suffer from treatment default.

Efforts should be made to understand the context of HIV testing, diagnosis, and care within the specific cultural and societal norms of the patient.

Information about HIV and HIV testing should be provided in the patient’s preferred language.

Source: Lieber et al., 2021

Without early diagnosis and management, many people with chronic HBV infection are at risk for developing HBV-related chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and extrahepatic disease, such as glomerulonephritis.

All newly arriving adult refugees who were born in or have lived in countries with ≥2% prevalence of chronic HBV infection – and adults ≥18 years of age who have risk factors – should be tested for HBV infection.

Most refugees are tested for HBsAg prior to departure to the US. Review overseas records for pre-departure testing and vaccination.

Hepatitis B

Many refugees arrive from countries where Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is highly endemic:

SOURCE: Jeng et al., Lancet, 2023

Parasites

The CDC offers Guidelines for Presumptive Treatment of ParasiteS. Special precautions must be taken with pregnant individuals – see ASTERISKS below.

All Middle Eastern, Asian, North African, Latin American, and Caribbean refugees:

For soil-transmitted helminths: Albendazole, single dose of 400 mg (200 mg for children 12-23 months) AND

For Strongyloides: Ivermectin, two doses 200 mcg/Kg orally once a day for 2 days

All African refugees who did not originate from or reside in countries where Loa loa infection is endemic:

For soil-transmitted helminths: Albendazole, single dose of 400 mg (200 mg for children 12-23 months) AND

For Strongyloides: Ivermectin, two doses 200 mcg/Kg orally once a day for 2 days AND

For Schistosomiasis: Praziquantel, 40 mg/kg, which may be divided in two doses

All sub-Saharan African refugees who originated from or resided in countries where Loa loa infection is endemic:

For soil-transmitted helminths: Albendazole, single dose of 400 mg (200 mg for children 12-23 months) AND

For Schistosomiasis: Praziquantel, 40 mg/kg, which may be divided in two doses

For Strongyloides: Refugees from Loa loa-endemic countries in Africa should not receive presumptive ivermectin for strongyloidiasis prior to departure. If Loa loa cannot be excluded, management should be deferred until arrival in the United States -OR- albendazole 400 mg twice a day for 7 days.

For the presumptive treatment of malaria (P. falciparum):

Refugees from sub-Saharan Africa receive presumptive treatment within 3 days of departure (primarily artemisinin-based combination therapy)*

*Albendazole and Ivermectin are pregnancy category C drugs and should NOT be administered as presumptive medications to pregnant women. Presumptive treatment with ivermectin should not be administered to women who are breastfeeding during the first week after birth.

**Excluding pregnant women and infants <5kg.

Review local confidentiality laws with all adult and adolescent patients.

Urine pregnancy testing should be performed for all women and girls of childbearing age.

Clinicians should counsel women of child-bearing age on the importance of taking a women’s multivitamin that includes folic acid.

Discuss family planning and available contraceptive methods. Condoms should be offered.

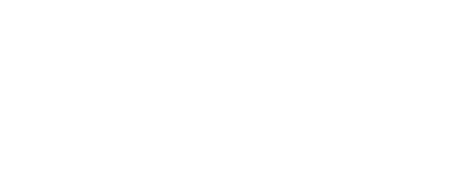

Many refugee women come from countries where female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is widely practiced. Screen women and girls from countries where FGM/C is practiced for associated medical complications, such as fistulae.

A complete evaluation for all STDs should be conducted. Consider STD testing for any refugee (including children) who has a history of sexual assault (including incest or underage marriage).

Sexual & Reproductive Health

Important care for all refugees:

Source: CDC

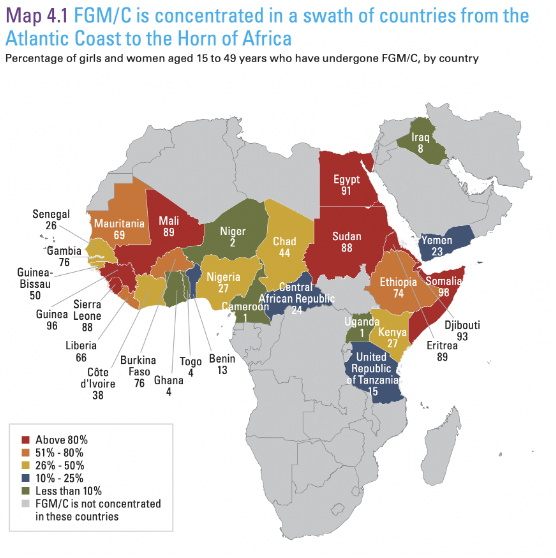

Cervical Cancer

Important information for female patients:

Most refugee women originate from countries that lack effective national cervical cancer control programs, including primary prevention of cervical cancer by HPV vaccination and secondary prevention through cervical screening.

Source: Singh et al., 2023

Although precise prevalence estimates range across studies, ~1/3 asylum seekers and refugees experience depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD. Depression may manifest as pain or other somatic symptoms.

As many as 44% of refugees, asylees, and asylum seekers are survivors of torture.

Refugees, displaced persons, and other migrants are more likely to have been victims of sexual violence, rape, and torture, either in camps or during the process of resettlement.

Women are particularly vulnerable in camps, where shelters may not be secure and they have to walk long distances to find items like firewood. Sexual violence remains a constant threat throughout their journey prior to resettlement.

The goal of the domestic mental health screening is to identify and evaluate refugees in need of mental health support and assistance.

It is recommended that clinicians consider one of the following two approaches for the initial refugee mental health screening:

Use of a single tool that screens for a wide range of symptoms associated with diverse potential DSM diagnoses (e.g., Refugee Health Screener-15 [RHS-15]); OR

Use of a combination of tools (e.g., screen for PTSD, anxiety, and depression separately), with each focused on a narrow range of symptoms and potential diagnoses.

Some refugees may not be literate or may need assistance understanding the meaning of questions or response options.

Based on available overseas records and findings of the domestic mental health screening, a referral to a mental health provider may be appropriate.

Mental Health

Mental health disorders are highly prevalent among refugees and other displaced persons:

Nutrition & Growth

The main goal of nutritional status screening of refugees after arrival is to identify those with nutritional deficiencies that require further evaluation and/or treatment:

Initial screening / management should include:

A complete history should document dietary habits, restrictions, and cultural dietary norms; food allergies; and any current or past nutritional deficiencies.

Anthropometric measurements including weight, and height/length for children.

Examination for specific physical findings indicating undernutrition/overnutrition or micronutrient deficiencies.

Initial laboratory screening for nutritional status of refugees should include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, including red blood cell indices.

All children 6 months to 59 months of age should be prescribed an age- appropriate daily multivitamin.

Refugees are particularly vulnerable after arrival and may not understand the complex health and social safety nets available to assist with access to food; enrollment in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and food stamps may be essential.

Children with clinical evidence of undernutrition should undergo a comprehensive medical and nutritional evaluation and referral for nutritionist and specialist care.

Refugees >6 years of age with clinical or laboratory evidence of poor nutrition may benefit from a multivitamin or specific supplementation according to published standards of practice.

Culturally appropriate nutritional counseling and social support for food access should be provided.

Lead is a known neurotoxin. Refugees could be at increased risk because of occupational and personal exposures to lead.

In many countries where refugees originate, environmental lead hazards are common, e.g., leaded gasoline, industrial emissions, lead-based paint, burning of waste containing lead.

Occupational hazards include living near or working in mines.

Household and personal use items associated with increased lead levels include car batteries used for household electricity, lead-glazed pottery and cooking pots.

Refugees may use or consume products contaminated with lead, such as traditional remedies, herbal supplements, spices, candies, cosmetics, and jewelries or amulets.

An initial lead exposure screening blood test should be performed for:

All refugee infants and children ≤16 years of age;

Refugee adolescents >16 years of age if there is a high index of suspicion or clinical signs/symptoms of lead exposure;

All pregnant or lactating women and girls.

Lead Screening

Screening for lead is a critical component of refugee care:

Tuberculosis (TB): She has a negative chest x-ray and no symptoms of active TB. Her IGRA came back positive. She has never received treatment for LTBI.

HIV: Negative.

Viral Hepatitis: Screening shows evidence of immunity to HAV; HBsAg-negative with no evidence of immunity to HBV.

Parasites: No prior treatment. Rapid diagnostic for malaria was negative, CBC was negative for eosinophilia, stool test O&P positive for hookworm.

Sexual and reproductive health: Pregnancy test negative. Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis screening negative.

Mental health: Screening consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) associated with witnessing the massacre of her family and being raped in a refugee camp.

Nutrition: She has difficulty accessing sufficient, nutritious food.

Lead: Venous lead normal.

Diagnostics

evaluating your patient’s examination:

Discussion

What would be your management and treatment recommendations?

Tuberculosis: Initiated treatment for LTBI.

Viral Hepatitis: Initiated HBV vaccination series.

Parasites: Provided albendazole to treat hookworm, in addition to presumptive treatment for strongyloides (ivermectin) and schistosomiasis (praziquantel).

Sexual and reproductive health: Follow-up visit scheduled for gynecological exam and pap smear.

Mental health: Referred to mental health specialist. Provided with information about the local refugee community center and refugee support groups.

Nutrition: Prescribed multivitamin. Met with social worker to register for food assistance program.

Management & Treatment

Your patient was cared for in the following ways:

The medications used to treat LTBI in the US include Isoniazid (H), Rifapentine (P), and Rifampin (R).

Short-course, rifamycin-based, 3- or 4-month LTBI treatment regimens are generally preferred over 6- or 9-month isoniazid monotherapy. Short course regimens include:

Three months of once-weekly isoniazid plus rifapentine (3HP)

Four months of daily rifampin (4R)

Three months of daily isoniazid plus rifampin (3HR)

Short-course treatment regimens have higher completion rates than longer 6 to 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy, and generally have a lower risk of hepatotoxicity.

If short-course treatment regimens are not an option, 6H and 9H are alternative, effective latent TB infection treatment regimens.

LTBI Treatment

Treating latent TB infection entails the following:

Reducing host vulnerability / susceptibility (host factors):

Optimize medical, nutritional, and mental health status

Improve health literacy

Reducing exposures / improving environments (environmental factors):

Maximize social supports

Improve access to nutrition

Screen for housing hazards

If working, screen for workplace hazards

Prevention

ADDRESSING HOST AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS FOR YOUR PATIENT:

Agencies & Organizations

support your patient in accessing supportive resources:

Community agencies can include resettlement agencies, newcomer centers, refugee advocate groups and forums, cultural centers, religious centers, and public libraries.

Clinicians can learn about resettlement agencies in their county and work with their institution to establish relationships.

Refugees selected for resettlement through the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program are eligible for Reception and Placement (R&P) assistance upon arrival in the U.S.. Refugees are sponsored by one of ten non-profit resettlement agencies participating in the R&P Program under a cooperative agreement with the Department of State.

Clinicians can utilize the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. ORR can offer resources and direct clinicians to the right contacts.

Beyond the Clinic

Your patient's story is part of a bigger picture:

Factors contributing to displacement: conflict/violence (9.8m) and disasters (30.7m).

Both conflict and displacement can be fueled by climate change. 95% of conflict-related new displacements occurred in countries with a high or very high vulnerability to climate change according to the ND-Global Adaptation Initiative Index (ND-GAIN). The ND-GAIN Country Index assesses a country's exposure, sensitivity and capacity to adapt to the negative effects of climate change.

Climate change is causing new humanitarian crises and accelerating existing ones in vulnerable communities around the world.

Source: Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) and the World Resource Institute (WRI) analyzed where climate crises are likely to occur and whether affected countries have the capacity to respond and protect vulnerable communities. Countries with low levels of climate readiness and high levels of fragility are most at risk of climate disaster. Climate readiness is measured by examining the threats that climate change poses to a country and that country’s ability to protect its citizens from climate disasters. Fragility is the likelihood that a country will collapse and become unable to govern or provide services to its citizens.

10 countries (see below) are considered particularly vulnerable to climate change. Collectively, these countries contribute just 0.28% of global CO2 emissions and make up 5.16% of the world’s population.

Somalia: Climate change has had a devastating impact on challenges of drought and extreme food insecurity. Political instability has made it difficult to address the climate crisis and protect vulnerable communities. By mid-2023, more than 8 million Somalis (nearly half the population) will be experiencing crisis levels of food insecurity.

Syria: Over a decade of war has eroded the country’s ability to respond to crises. The conflict and an intense economic crisis have forced 90% of Syrians below the poverty line. Extreme drought and the February 2023 earthquake near the Syrian-Turkish border, which affected hundreds of thousands of Syrians, have highlighted the challenges associated with responding to emergencies in an already fragile country.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Ongoing conflict, economic challenges and disease outbreaks are persistent challenges. Over 100 armed groups fight for control in eastern Congo, often targeting civilians. Major disease outbreaks–including measles, malaria and Ebola– pose a threat to a weakened health care system and put many lives at risk. These factors have weakened the country’s ability to prepare for climate disasters and have disrupted humanitarian support while citizens face floods and rising food insecurity.

Afghanistan: The country has experienced growing fragility as foreign aid is disrupted and an economic collapse deepens poverty. Afghanistan has entered its third year of drought while intense flooding in some parts of the country has diminished food production and driven people from their homes.

Yemen: Years of conflict have driven an economic crisis and high levels of fragility. By the end of 2022, 17 million people in Yemen required food assistance, while 1.3 million pregnant or breastfeeding women and 2.2 million children required treatment for malnutrition. Climate change has worsened desertification and drought in the country.

Chad: The world’s most climate-vulnerable country on the ND-Global Adaptation Initiative Index. Flooding in 2022 affected >1 million people while an economic crisis has led to widespread food insecurity. Growing conflict and political tensions have limited progress in building climate resilience.

South Sudan: A country with high fragility and low climate readiness, that is increasingly vulnerable to climate disasters. While the civil war officially ended in 2018, local conflicts remain widespread. Better climate resiliency is needed to protect South Sudanese citizens from climate shocks, like the severe floods which affected over 900,000 people in late 2022.

Central African Republic: Competition for control over political power and natural resources has destabilized the country. Severe flooding threatens the safety and health of residents, particularly those living in camps for internally displaced people, by contributing to the spread of water-borne illnesses like cholera. Other diseases like malaria, meningitis and monkeypox also strain the weakened health system.

Nigeria: Flooding in late 2022 affected 2.5 million people and caused extensive damage to the country’s farmland. By mid-2023 an estimated 25 million Nigerians will face high levels of food insecurity. Political tensions and widespread conflict have contributed to the country’s fragility, making it difficult to respond to climate disasters.

Ethiopia: Drought is affecting >24 million Ethiopians. This number is expected to rise as the country is set to enter its sixth consecutive failed rainy season. Numerous conflicts across the region and political instability have disrupted humanitarian support in the country and made it difficult for authorities to address the impacts of climate change.

Call to Action

Clinicians can take action to advance planetary health:

At the clinic:

Ensure clinicians are trained in refugee health principles

Ensure culturally sensitive services are available

Ensure reportable diseases are reported to public health

Work with social workers to identify key agencies in the area that can support refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants

In your community:

Work with community agencies to ensure that appropriate referrals are being made for persons to receive screening and treatment

Ensure that appropriate referrals are being made for screening and treatment

At the societal level:

Raise awareness of the drivers of forced migration, including climate change

Summary and

Key Learning Points

also available for download here:

General approach:

Consider cultural & language issues

Address specific risks :

Mental health

Parasites

Nutrition & growth

Lead screening

Sexual & reproductive health

Key points in history:

Offer interpreter services and reassurance

Determine geographic history, circumstances of departure, possible exposures en route

Patient’s stated age and reported date of birth may not be accurate

Consider different health-seeking behaviors, terminology

Consider traditional medicines, herbs, tinctures, etc.

Patient may use different terminology for symptoms

Consider prior living circumstances, food and water sources, animal & environmental exposures, prior occupation(s), traditional practices, current housing

Substance use: Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, stimulants such as Khat, Kola nuts

Consider patient’s social support, as well as education & literacy (can patient read prescription instructions?)

Legal status: Pre-departure screening and health services

Sensitive topics: Sexual history, trauma or abuse, torture, rape, witnessed violence

Physical exam tips:

Amputations or deformities related to land mines or other explosives

Cultural health practices – e.g., cupping, coining – may mimic torture, physical abuse

Common diagnoses:

Latent TB

Active TB

Hepatitis B

Malaria

HIV

Hypertension

Mental health disorders

Soil transmitted helminths

Schistosomiasis

Dental, ophthalmologic problems

Preventative care:

Host factors:

Optimize medical, nutritional, and mental health status

Ensure vaccinations up to date

Improve health literacy

Environmental factors:

Maximize social supports

Improve access to nutrition

Screen for housing hazards

If working, screen for workplace hazards

Call to action:

In the clinic:

Ensure clinicians are trained in refugee health principles

Ensure culturally sensitive services are available

Ensure reportable diseases are reported to public health

Work with social workers to identify key agencies in the area that can support refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants

In your community:

Work with community agencies to ensure that appropriate referrals are being made for persons to receive screening and treatment

At the societal level:

Raise awareness of the drivers of forced migration, including climate change

Additional Resources

Refugees who enter the United States through the official resettlement process must undergo a health screening before entering the country (done by International Organization for Migration). The CDC offers a profile for specific countries that contains detailed information to assist various stakeholders, including clinicians, working on medical screening for refugee health.

The University of Minnesota with support from the CDC launched the National Resource Center for Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants (NRC-RIM) which has a wealth of information and resources for clinicians working with refugees and immigrants from cultural competency to language appropriate educational material.

CareRef is a toolkit to guide clinicians through the process of conducting a routine post-arrival medical screening of newly arrived refugees.

Resettlement and Placement Agency contacts available here.

References

2022 Global Report on Food Crises

42 U.S.C. United States Code, 2011 Edition. Title 42 - THE PUBLIC HEALTH AND WELFARE CHAPTER 6A - PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE SUBCHAPTER II - GENERAL POWERS AND DUTIES Part G - Quarantine and Inspection. Available at: Govinfo.gov.

Alberts CJ, Clifford GM, Georges D, Negro F, Lesi OA, Hutin YJ, de Martel C. Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among patients with cirrhosis at country, region, and global levels: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;7(8):724-735.

Araujo JO, Souza FM, Proença R, Bastos ML, Trajman A, Faerstein E. Prevalence of sexual violence among refugees: a systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2019 Sep 23;53:78.

The Asylum Medicine Training Initiative offers free training in FME https://asylummedtraining.org/

Barnett ED, Weld LH, McCarthy AE, et al. Spectrum of illness in international migrants seen at GeoSentinel clinics in 1997-2009, part 1: US-bound migrants evaluated by comprehensive protocol-based health assessment. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(7):913-924. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1015

BMA.org.UK- Refugee and asylum seeker patient health toolkit

Boggild AK, Geduld J, Libman M, et al. Spectrum of illness in migrants to Canada: sentinel surveillance through CanTravNet. J Travel Med. 2019;26(2):tay117. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay117

Borisov AS, Bamrah Morris S, Njie GJ, et al. Update of Recommendations for Use of Once-Weekly Isoniazid-Rifapentine Regimen to Treat Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:723–726.

CDC Refugee Health. www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/refugee-guidelines.html

Collinet-Adler, S., et al., Financial implications of refugee malaria: the impact of pre-departure presumptive treatment with anti-malarial drugs. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2007. 77(3): p. 458-63.

Crosby, S.S. (2013), “Primary Care Management of Non-English-Speaking Refugees Who Have Experienced Trauma: A Clinical Review”, The Journal of the American Medical Association310(5), pp. 519-528.

De Schrijver L, Vander Beken T, Krahé B, Keygnaert I. Prevalence of Sexual Violence in Migrants, Applicants for International Protection, and Refugees in Europe: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of the Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Sep 11;15(9):1979.

Elmore CE, Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM. Health Inequity in Cervical Cancer Control Among Refugee Women in the United States by Country of Origin. Health Equity. 2021 Mar 4;5(1):119-123.

Ethnomed: http://ethnomed.org

Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005 Apr 9-15;365(9467):1309-14.

For TB resources and guidelines: See American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and state TB control programs

https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/profiles/index.html

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/extracontinental-migrants-latin-america

https://www.rescue.org/article/crisis-somalia-catastrophic-hunger-amid-drought-and-conflict

https://www.rescue.org/article/10-countries-risk-climate-disaster

https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends

https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

https://www.unrefugees.org/

https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/camps/

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/refugee-and-migrant-health

https://www.who.int/news/item/25-01-2023-one-stop-resource-toolkit-launched-on-refugee-and-migrant-health

IDMC Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021: Internal displacement in a changing climate

Jeng WJ, Papatheodoridis GV, Lok ASF. Hepatitis B [published online ahead of print, 2023 Feb 9]. Lancet. 2023;S0140-6736(22)01468-4.

Kharwadkar S, Attanayake V, Duncan J, Navaratne N, Benson J. The impact of climate change on the risk factors for tuberculosis: A systematic review. Environ Res. 2022;212(Pt C):113436.

Kleinert, E., Müller, F., Furaijat, G. et al. Does refugee status matter? Medical needs of newly arrived asylum seekers and resettlement refugees - a retrospective observational study of diagnoses in a primary care setting. Confl Health 13, 39 (2019).

Lieber, M., Chin-Hong, P., Whittle, H.J. et al. The Synergistic Relationship Between Climate Change and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: A Conceptual Framework. AIDS Behav 25, 2266–2277 (2021).

Lieber, M., Chin-Hong, P., Whittle, H.J. et al. The Synergistic Relationship Between Climate Change and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: A Conceptual Framework. AIDS Behav 25, 2266–2277 (2021).

McCarthy AE, Weld LH, Barnett ED, et al. Spectrum of illness in international migrants seen at GeoSentinel clinics in 1997-2009, part 2: migrants resettled internationally and evaluated for specific health concerns. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(7):925-933. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1016

Mental Health Facts on Refugees, Asylum-seekers, & Survivors of Forced Displacement. Statement from the Amercian Psychiatric Association.

Nöstlinger C, Cosaert T, Landeghem EV, et al. HIV among migrants in precarious circumstances in the EU and European Economic Area. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(6):e428-e437.

Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 63, Issue 7, 1 October 2016, Pages e147–e195.

Ravanfar, P. and and Dinulos, J.G. Cultural practices affecting the skin of children. Curr Opin Pediatr 22:423–431, 2010.

Relief Web: United Nations website providing information for humanitarian relief organizations. Updated daily. http://reliefweb.int/

Responding to the Challenge of Non-communicable Diseases. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Ross J, Cunningham CO, Hanna DB. HIV outcomes among migrants from low-income and middle-income countries living in high-income countries: a review of recent evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb;31(1):25-32.

Sexual violence against refugee women on the move to and within Europe. World Health Organization. www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/319311/9-Sexual-violence-refugee-women.pdf

Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, et al., Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health. 2023 Feb;11(2):e197-e206.

Spearman CW, Afihene M, Ally R, et al. Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(12):900-909.

Sterling TR, Njie G, Zenner D, et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020;69(No. RR-1):1–11.

The United States Office of Refugee Resettlement, cited in “In Their Own Voices: Honoring Survivors of Torture”. International Rescue Committee, 2021.

Turrini G, Purgato M, Ballette F, Nosè M, Ostuzzi G, Barbui C. Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017 Aug 25;11:51.

UNHCR - Strategic Framework for Climate Action

https://www.unhcr.org/604a26d84.pdf

UNHCR and International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change joint Factsheet (2020) Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge and Climate Adaptation

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). www.unhcr.org

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). www.unocha.org/

Wagner KS, Lawrence J, Anderson L, et al. Migrant health and infectious diseases in the UK: findings from the last 10 years of surveillance. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;36(1):28-35. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdt021